Last week I attended the ICIDS 2015 conference in Copenhagen. The conference was about academic research on Interactive Digital Storytelling (IDS) which is very close to what we call Interactive Fiction, with some key differences. The topics revolved mostly around making computer-generated story content, emergent gameplay, and autonomous non-player characters. In a nutshell you could say that while IF is about using computers to tell stories, IDS is more about making computers tell stories.

The IDS people seem to be well aware and at least superficially following the IF scene. People like Emily Short, Squinky and Porpentine were mentioned several times. Inklewriter was used to build a game in one study. The interest is naturally in things that are close to the areas of research, so games that have something to do with computer-assisted content generation are the ones that get most attention.

All conference papers can be downloaded here. The ebook download is available for free for an unspecified time so it's best to grab it while it's there. Once the offer expires the download will cost more than 50 €.

The defining dilemma with IDS seems to be that computer-generated content is often random and incoherent in contrast to human-written narrative. On the other side of the scale you have generated content that's random but allows for emergent stories, and on the other side there's human authored content that's coherent but restricts the story to the pre-written plot. A lot of effort is going into bridging this gap so that generated narrative would have the best of both worlds: highly emergent plot that's still a coherent whole.

One of the suggested approaches (Ryan et al) was detecting sensible plots from a story world where many players or autonomous NPCs interact with each other and create emergent content. Dwarf Fortress was used as an example of such world. The method was to analyze things like when individual events happened and what kind of narrative tension the events had. This was a just a theoretical idea at this point so there wasn't yet any actual algorithm that could do this.

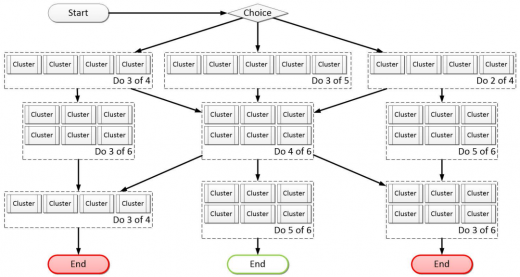

Hartmut Koenitz has taught interactive narrative classes using his own ASAPS system which seems to be one of the more mature projects, although it's available on request only. He has identified some tendencies that his students have when writing interactive stories:

- Tendency to build strictly non-convening branches: the story branches but there's always only one path to a given passage (traditional CYOA book style)

- Strong binary choices ("do you a) give your money to charity or b) become a crime lord") instead of more nuanced options

- Mechanistic pacing: each passage ends in a choice

- Narcissistic content: the students want every reader to see all content the game has

Koenitz also talked about how effective temporary removal of control can be for an interactive story. If you sometimes take away control from players, the control they are left with becomes more precious to them.

Alex Mitchell analyzed reflective rereading of digital narrative, and presented three types of motivations for rereadings:

- Partial rereading: rereading because you can piece together more of the story after you've seen the whole thing (e.g. Memento)

- Simple or unreflective rereading: you want to recapture the experience you had the first time

- Reflective rereading: having seen the work before, you know what it's about and want to view the work with that extra information, for example to identify details that might have been missed the first time (e.g. 6th Sense)

He also identified three types of experiences from generated or highly varying interactive narratives:

- Eliza effect: The system looks complex but is actually simple. Telltale's games were used as an example of this: at first playthrough they seem to offer a large degree of choice, and the games do their best to reinforce this interpretation (periodical "They will remember this" notifications for example), but on replay it becomes evident that the plot is actually largely predetermined.

- Tale-Spin effect: The system looks simple but is actually complex, and the player may never become aware of the underlying complexity.

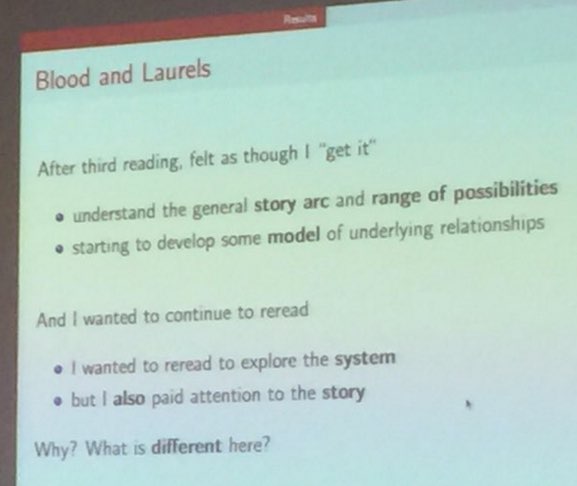

- SimCity effect: The system is complex and works with the player to build up understanding of the complexity. Emily Short's Blood and Laurels was used as an example of this type of game.

New Dimensions in Testimony is a project that has filmed interviews of a holocaust survivor. A holographic projector shows him in 3D and you can ask questions that are interpreted with voice recognition software. The aim is to replicate a face-to-face conversation as accurately as possible so that people can have that experience even after it's not physically possible anymore.

The end result looks like something out of Star Trek, and the numbers are impressive: the system has 1700 different responses and testing showed that there was an appropriate answer 95% of museum visitors' questions in the database, although due to speech recognition and language parsing issues the system replied correctly only two thirds of the time. They were confident that question understanding can be further improved.

Kate Compton talked about her generative text tool, Tracery, and announced a new IDE for it at tracery.io. It basically takes a certain data structure and generates variations based on the list of text strings given:

{

"origin": [

"#location# you can see a #landmark#."

],

"location": [

"Behind the #building#",

"Far ahead",

"Somewhere in the distance",

"Nearby"

],

"building": [

"house",

"shack",

"gazebo",

"garage"

],

"landmark": [

"river",

"forest",

"beach",

"hill",

"lake",

"swamp",

"mountain range"

]

}

The placeholders (#location#, #landmark#, #building#) would be replaced with random items in the lists, resulting in e.g. "Behind the gazebo you can see a beach" or "Far ahead you can see a swamp."

Tracery is probably best known as the main component of Cheap Bots Done Quick which is a Twitter bot making service. I tried it out and made a couple of Twitter bots, and it really lives up to its name: it took less than an hour in total and most of that time went in trying to find suitable word lists.

Here's to the costive ones. The fencings. The Barrymores. The middle ages. The echoic schoolbags in the colorful art class.

— Here's To Bot Ones (@HeresToBotOnes) 13 Dec 2015

I Have No Ear, and I Must Crosscut

— I Have No X I Must Y (@ihavenobot) 13 Dec 2015

Elizaveta Shkirando from Ubisoft talked about "betatesting" story elements in games. Usually in AAA game development narrative elements have low priority and story writers are brought in at a late stage when it's practically too late to get feedback. Ubisoft has tried to change this by making it possible for writers to get narrative feedback much earlier.

The writers made a 5-10 page long summary of the script (which was not too big and not too vague) that was given to two groups. The first group was writers not involved in that particular project, and the second group the game's designers who weren't directly involved with writing the script. The groups were able to make notes to the script, ask questions from the writers, and then answer a questionnaire that had evaluations like:

- Appreciation: "I enjoyed this section of the script."

- Comprehension: "I understood what was happening in this section of the script."

- Interest: "I want to know what happens next in the story."

- Character motivation: "I understand the protagonists motivations in this part of the story"

- Character progression: "I understand what the protagonist must do next."

The questionnaire repeated after every section of the script, and at the end there was a final questionnaire that had questions about overall likes and dislikes, most memorable moments, satisfaction with the story's ending and so on. Afterwards the testers who gave the most interesting and insightful comments were invited to a group discussion with the writers.

Shkirando also stressed that it's important to ask and receive positive feedback as well instead of just lists of problematic issues. This helps the writers to not lose the good parts when they're fixing the problem areas.

Melissa Roemmele showed a story writing assistant that could help alleviate writer's block by adding a new sentence to the story on demand. The corpus is about 20 million stories collected from blogs, consisting of in total about 700 million sentences. The software analyzes the story that's being written and picks a sentence that seems to be the best fit for the context.

It's uncertain how well the tool would work in practice, but it would be at least a cool toy to play with. Unfortunately it's not publicly available.

In addition to the presentations, there were posters and game demonstrations. Some of the games were more traditional and not necessarily about interactive narrative, at least in the traditional sense. Here are a couple of picks:

An "interactive documentary game" that lets you make a documentary about a crime organization. The material for it is real and they're filming it right now. The release is set to next year but the feature list seemed so ambitious that it seems likely that 2016 is an overly optimistic target.

Blue Behold by Karleen Groupierre is a physical setpiece that's "painted" by a video projector. It comes with glasses that track eye movements: a spotlight follows the player's gaze and interacts with the environment. It's really beautiful and fun to play. Too bad the set's physical size and special equipment mean you need access to the original work to be able to play it.

Don't Let Them Die by Rob Homewood is equal parts artwork and game. The game consists of a flock of birds flying around a pretty landscape. It pulls stock data from the Internet every minute, and if it detects a massive drop in stock prices in a short period of time, the birds die. Therefore you play the game by preventing stock market from crashing: by being part of society and consuming.

It could of course be debated whether the humankind can play a game like this, or whether it's a game at all. As an art piece it's multifaceted and thought-provoking; easily the most interesting demo in the conference.

The problem with a lot of academic software projects is that they're built for the purposes of a single, often very narrow, research project. It might be about, for example, a single aspect of autonomous NPC behavior, and a game is made focusing on that only. The end result is either a short demo that looks very interesting but isn't complete, or a system that does that one thing they're studying but isn't really usable in real world applications. It seems very similar to what happens with IntroComp games: when asked about it, every single author says that afterwards they're going to expand and release the game or tool they've created, but in real life that happens about as often as an IntroComp game gets a full release.

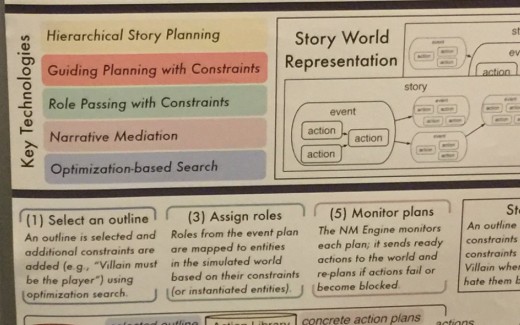

One project from Reykjavik University looked very promising: it aims to combine all these small projects into one complete system that could be used to make real games. It includes five different technologies that are way beyond my understanding, but apparently the end result would be a tool to make complete simulated story worlds.

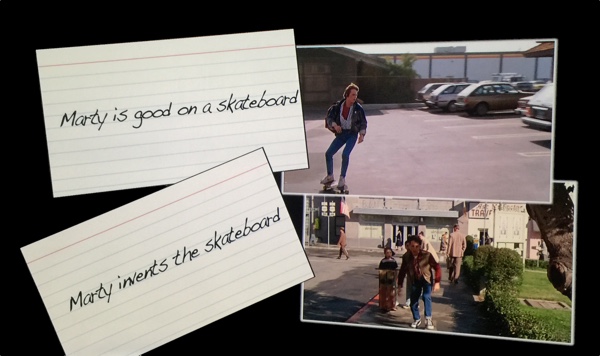

Common writing advice is to always avoid clichés, but that's too simplistic to accept as a universal rule. Clichés and sterotypes serve to support another advice: Show, don't tell.

Common writing advice is to always avoid clichés, but that's too simplistic to accept as a universal rule. Clichés and sterotypes serve to support another advice: Show, don't tell.